At the urging of Russian journalist Konstantin Chilikin, I accidentally wrote an exhaustive history of the rock group Panic, the third installment of which is printed below. It was fun to write, even if I’m the only one who actually read all the way to the bottom. Perhaps there will yet be another chapter…

Now let’s skip a couple of years: Record II, Medocine, California. You’re doing you vocal parts for the “Fact” album. This time Marc Senasac is in position of producer. What can you remember about the atmosphere in the studio? Would you say that you saw the beginning of the end already? The album “Fact” sounds to me more matured in terms of music and heavier in terms of production. Would you agree with me? How important were cover artworks for you? Did you pay attention to them? Did you have a chance to say your word and share opinions with Metal Blade Records about what you’d like to see on the covers? Did you play enough shows in support of your albums? Were there any tours with bigger bands? Did you play outside your area? Did you get any offers to play live in Europe? Why did the band split-up? Was it because of Grunge or were you tired of constant struggle for survival in music business? Tell me please about your life after Panic. As far as I understand you own construction business. Does it mean that you quit music entirely?Do you still stay in touch with Marty, George and Jack? Is there any chance to see re-issues of both CDs by Panic? Feel free to say anything you like to round up this interview:

FACT

We seemed to be finished with long tours by Christmas 1991. Bill Graham had died tragically while we were on the Nuclear Assault tour, and BGP was a bit of a mess. Toni was having trouble enough getting support for Exo. We were not her priority…

So we went back to doing what we knew best—namely writing kickass songs and killing it live locally. By that time, we were established enough to get opening slots on the better touring metal bills, and we had the good fortune to share Seattle stages with White Zombie, Heathen, Suicidal Tendencies, Soundgarden, and Dee Snider’s Widowmaker. We did a leg of dates in California with Testament and even opened for Pantera at the Stone in San Francisco.

Cowboys from Hell was easily the most-impactful record ever on Panic’s development. George had been into Mach I , before Phil was in the band. They were good even then, but what happened to them between their first record with Anselmo and Cowboys was a pretty stark transformation. Phil cut his hair, they ditched the spandex, and proceeded to craft this sound that was unlike anything that had come before it. It seemed like every five years or so– in that particular golden age of heavy metal—a band would come out that would set a new standard for heavy. In the late ‘70s it was Motorhead, the early ‘80s Iron Maiden. Late ‘80s Metallica. And then in the early 1990s here was this record that was so loud & sharp & punishing that it sounded like a hyper-coiled version of the band was inside your speakers playing it live. The production on Cowboys from Hell made everything that had come before it sound 3rd World. And it wasn’t just the sounds. The songs and the performances were so good—we could hardly believe it was real.

I wouldn’t say that record influenced our writing as much as it did our sonic aspirations. Our new batch of songs was already taking shape and it definitely sounded like the second Panic record and not like the follow-up to Cowboys from Hell. We knew where we were going musically. But we wanted those tones.

Very unfortunately, we were not able to get them. Pantera had years of experience experimenting in their own studio. They had a major label budget and they had Terry Date. We didn’t have any of those things.

We went to Mendocino in October 1992 to make Fact. The studio, Record II, was supposedly an exact replica of Quincy Jones’ Record I in Los Angeles. It was a nice room—great space. There was lots of space outside the studio, also. The overall atmosphere could not have been more different than the one in which we recorded Epidemic. Mendocino is a picturesque coastal town of 700 people, on the northern shore of California. The studio was on a sprawling acreage in the woods, which was also dotted with cabins which served as dormitories. In San Francisco, we had slept two-to-a-bed for three weeks. In Mendocino, we each had our own cabin, hundreds of feet from the next guy.

This might have been a productive atmosphere for some projects. It wasn’t for ours.

As with the first record, the band was prepared. Basic tracks were slain quickly and we settled down to vocals and sweetening. There was more improvisation in these sessions—more experimentation with sounds, effects and even arrangements. As with the Epidemic experience, I had a little trouble finding a vocal groove. Unlike Epidemic, I never really found one.

The lesson I thought I’d learned recording Epidemic was that I didn’t need to press. There was plenty of time, and I didn’t have to get all my parts sung in a day. This was even more true in Mendocino, with more space and a more-forgiving budget. There was time to try something out and then go back the next day and re-do it if it didn’t sound good. Unfortunately as a result, there was more day-drinking and less focus on my part. My perspective on the songs wasn’t as keen as it had been going in to the Epidemic sessions, and by the end of the project, any perspective I did have was totally shot. I wasn’t able to step outside my role, and I didn’t know if it was any good or not.

As it turned out, it wasn’t. In fact, it was fairly awful. I haven’t listened to that record in years– it’s just too painful. The songs and the musical performances are really good. But the singing is pinched and tuneless. There’s no character to it at all. No color or humor. It fuckin’ blows…

We finished tracking on Halloween night 1992. We killed the rest of the bourbon and put on KISS makeup and ended up hitting golfballs in a steady rain at dawn on November 1st. I remember Toni leaving that morning, shaking her head. I think she knew the record wasn’t very good.

I didn’t really know it yet. Back home in Seattle while we were waiting to go mix, I convinced myself that the raw mixes were flat and that the finals would pop. Then Marty & I went back to the Bay Area and made matters even worse.

We were striving for that sound. Vulger Display was out by now, and though we didn’t like the songs on that record nearly as much as those on Cowboys, we still wanted that sound. Unfortunately, we didn’t have the budget, producer or experience to get it. And what we ended up with instead was a thin, clicky imitation. Plastic and practically unlistenable in my opinion.

The packaging of the record ironically turned out killer. As on Epidemic, the idea for the title was Marty’s. The concept of Fact was a stark, undeniable truth. Fact. No getting around it. In your face, in your shit.

Custom culture darling Frank Kozik was commissioned to do the cover art. Kozik was popular in the underground at the time, but metal was not something he was associated with. Kozik was famous for his colorized photographs, and he sent us a stack of fucked-up images to choose from. The one we selected was ghastly. Like a lot of Frank’s stash, the photo was of the scene of an accident. It pictured a horrified woman, the wife/mother of a father & son who had just been killed by the exploding tractor tire they’d been filling with compressed air. The cars in the background suggested the photo might have been from the late 1950s. The enormous tire was in the foreground, and the woman was looking directly into the lens of the camera, a scream on her lips.

We loved it! We were going to take our photos at a gas station and give out promotional tire gauges with Fact printed on them. There was just one problem: the woman in the photograph was still alive, meaning the image was not yet in public domain. We would need her consent to use the image or else risk a weighty lawsuit.

After some procrastination, Toni contacted the now old woman via telephone. Having to re-live the experience was hard on her, and ultimately she said she wouldn’t sign off unless it paid better than Metal Blade was willing to cough up. But Kozik had already made the silkscreen! There are a few copies of the image floating around to this day, but of course no records were produced with this cover. It was like Spinal Tap! We settled instead for the abstract image of the man lying under the straight chair. I love this cover and the related images from the inside of the package. Probably the only thing I do love about Fact. (We still did take the photos at a gas station…)

Toni dumped us soon after the album’s release, and we started working more closely with Soozy. She had a big heart and she loved us as individuals and as a band. She was getting us great shows at home, headlining bigger clubs on weekends. But we just didn’t have the national connections. We had a new record and we needed to get out on the real road. But we couldn’t find the onramp.

We went to California for a week’s worth of dates in July. A showcase in Los Angeles was a total flop and everyone at Metal Blade were mass fags, including Slagel. For the first time ever, I was totally bored and couldn’t wait to get away from the whole thing. The morning after the last show, I was scheduled to fly from San Francisco to visit my mother in Arkansas. As I tiptoed out of the hotel room at dawn, I smelled what I thought was the end. As it turned out, it was only Jack’s underpants, but it definitely smelled like the end of something. I remember looking back into the room at my snoring bandmates and crew, scattered across the tiny room at the Phoenix, open duffle bags and shit strewn everywhere. My neck and liver ached. I was broke. I’d lost my hat. I shook my head and closed the door gently behind me. I took a deep breath before limping down the stairs, past the pool, and out the front gate onto Eddy Street to hail a cab, the Tenderloin coming slowly to life in the early morning light.

When I got back to Seattle a couple of weeks later, the band met for drinks and looked at the facts, as they were. There wasn’t much to squeeze from this record. We had no tour support and no national press. Marty was listening to Exile on Main Street every day and I just wanted to cut my hair and play garage rock. George & Jack conceded. It’s hard to be a convincing metal band if your heart isn’t in it, and I for one had really had it. We decided it would be best to kill it before it killed us.

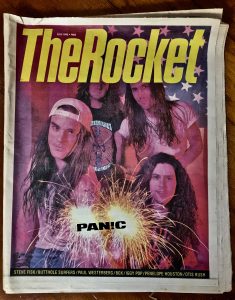

Ironically, we were on the cover of Seattle’s Rocket magazine at the time of the breakup. It was a pretty big honor to be on the cover of this beloved monthly periodical, and it felt weird to see it on the newsstand for the rest of July, knowing we were running out the clock. The band played its last show on Ocotber 9 at the Colourbox in Pioneer Square on a rich bill of friend’s bands. It was wild celebration—a kickass ending of a very loud era. I hadn’t washed my hair in weeks, knowing I was just going to shave it off after the show. I did.

In retrospect, we might have given it one more record. Three is kind of a magic number when it comes to breaking albums. There were some new songs taking shape, and we could have killed a year playing bars and hoping Metal Blade would pay for a third album. But the signs were bleak and we’d been working so hard for so long already. The timing felt right, and I  don’t think it was wrong.

don’t think it was wrong.

Marty immediately formed 50 Paces with some old friends. His project The Ones followed that before he joined the Supersuckers.

George hasn’t ever gone without a band, either, playing with the likes of Blacklist, Landfill, Chasing the Bullet and eventually Sanctuary.

Jack has stayed off the drum stool, at least as far as being in a working band. He’s been more interested in playing guitar & piano than drums as far as I know.

I had fun playing drums in a goofy garage band, then joined a project called HellCat with guys from Gruntruck and Poison Idea. Later, I hooked up with my garage rock heroes from the Mono Men to form Watts and we put out a record on Estrus in 1999.

I don’t own a construction company. I’m a limp-wristed Realtor now in Bellingham, WA just south of the Canadian border. I’ve been married for 22 years to the girl I was dating when Panic broke up and we have two wicked awesome kids, both musicians. My son actually played his first ever rock show with Marty at Pinky’s wedding when he was 8. So, you know—the apple don’t rot too far from the tree…

Thanks again for asking about Panic, Kon. I hope you don’t wish you hadn’t. It’s been fun to work on this history. I don’t know of how much interest it will be to your readers, but it’s been fun for me to re-live.

See you on the fence.

–jb

0 Comments on this post

Leave a Comment